Amazing Seals

Seal species

There are two native seal species in the UK: Grey and harbour seals. We are extremely lucky to routinely see grey seals, a globally rare seal species only present in the north Atlantic. The UK is home to 34% of the entire world’s population based on pup production (down from 50% when SRT began in 2000). Despite this, there are still fewer grey seals in the UK than red squirrels. 70% of UK seals breed in Scotland (down from 90%).

Harbour seals are only found in the northern hemisphere in both the Pacific and Atlantic. There are three recognised subspecies. Around 30% of the European harbour seals are found in the UK (down from 40% in 2002). Whilst harbour seals have been present in the SW since the Mesolithic, the first successfully weaned harbour seal pup was recorded in 2021 since SRT’s records began.

The UK is also visited by multiple ‘out of habitat’ vagrant seal species, including bearded, harp, hooded and ringed seals as well as the Atlantic walrus.

Legislation

On the IUCN Red List for endangered species, grey and harbour seals are protected by the Habitats Directive in the EU. This was transposed into UK law through a series of regulations, including the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017. In the UK, seals are also protected by the Conservation of Seals Act (making it illegal to ‘kill, injure and take’ seals) and have legal protection in Special Areas of Conservation and Special Sites of Scientific Interest (where it can also illegal to disturb seals and the habitat they use.)

Habitat

Grey and harbour seals can be found all around the UK coast – swimming and resting at sea or hauled out on beaches, offshore rocks, up estuaries, on sandbanks or hidden away in remote sea caves. Harbour seals appear to prefer more sheltered locations. Haul out sites are established seal hot spots routinely visited by seals as they move around the UK oceans. Each sensitive seal site contributes to a network of habitat that is vital to sustain individual seals as they move around their unique pathways during three seal seasons – the foraging, pupping and moulting season.

Why we all need seals to thrive

Seals are our most easily sighted iconic marine mammal, as they haul out in predictable places, at predictable times all year round and can be as nosy about us as we are with them. This makes them extremely important as ambassadorial species emotionally engaging us all with our precious marine habitat. Seals are sentinels bringing early warning stories to us on land about the state of their marine environment. As top predators, seals help to maintain crucial balance in the marine ecosystem upon which we all depend for air, food and water. Thriving seals, means thriving fish and thriving fisheries.

Seals make us smile, giving many a reason to exercise out and about and contributing to our health and wellbeing. Their huge public appeal makes them a key wildlife attraction with locals and visitors alike. As such seals make a very positive contribution to our ever expanding recreational and tourist based marine businesses and adding diversity to coastal economies.

Dive adaptations

Incredibly adapted for life at sea, native seals dive to depths of 300m. 15 seconds before they dive the can slow their heart from 120 beats to just a few beats a minute, effectively shutting off their circulation. Their pool their blood from their periphery into their core, using vital oxygen that they have stored in their both their blood hemoglobin and muscles myoglobin). Seals breathe out before they dive to avoid the bends when they dive to feed. Seals mostly forage on the sea bed for their preferred prey species: sand eels for grey seals and dragonets for harbour seals.

Seal senses

Seal senses are highly developed and finely tuned:

Smell

A seal’s nostrils are closed until it uses its muscles to open them to breathe in short bursts. When seals are sleeping, look out for the opening and closing of their nostrils. Seals perform sniff greetings with each other and mothers identify their pups this way, which is why it is important to not leave human or dog scent around a pup. Seals routinely sniff a beach when they arrive suggesting they may recognise familiar places this way from the unique bacterial scent making individual beaches identifiable. Seals have vomeronasal glands that suggests they may also be able to taste scents too (much like a cat).

(photo taken in rescue centre)

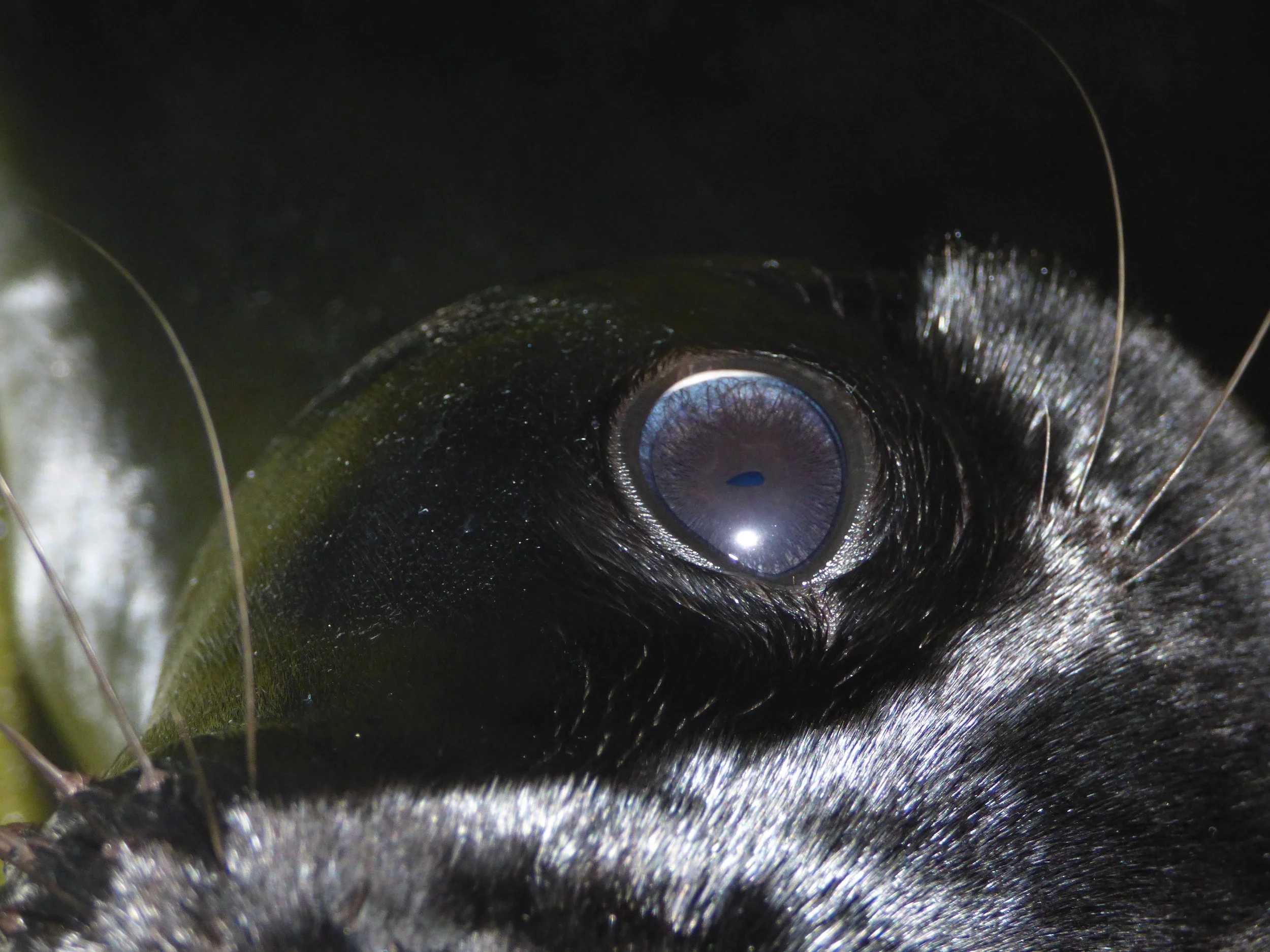

Sight

Seals have amphibious vision. Huge eyes and a tapetum lucidum (reflective retina) gather the maximum amount of light underwater. They have vertically slit pupils (much like a cat’s) and horizontally flattened corneas to enable them to see almost as well in air as in the sea. This means that seals can see us even when we are a long distance away. They do not seem to have much colour spectrum, but may be better able to detect contrasting features of their environment.

Hearing

A seal’s audible range is similar to that of humans in air. If you can hear them, they can hear you, so it is important to only talk in whispers when you are nearby. However, seals have amazing hearing adaptations too. When underwater they can pump blood into their inner ear enabling them to much higher frequencies underwater than in air.

Touch

Seal whiskers are more sensitive than your finger tips. Seals have over 700,000 nerve endings in their muzzles (compared to over 300,000 in our hands) and these enable blind seals to survive in the wild. Whiskers are a helical shape to expel water and precent vortices developing behind them. This enables them to hold their whiskers still enabling them to detect the wake of a fish 30 seconds in front and 180m away from them. Seals will also explore objects using their mouths and flippers.

Seal origins

Seals are related to cats, dogs otters and bears and were around long before humans (who have only been on earth less than one million years). Fossil evidence suggests that seals moved from the land through rivers and into the sea.

Taxomonic ranks: Animalia; Chordata (with a back bone); Mammalia (mostly feed young on milk); Carnivora (animal protein diet); Pinnipedia (fin or flipper footed)

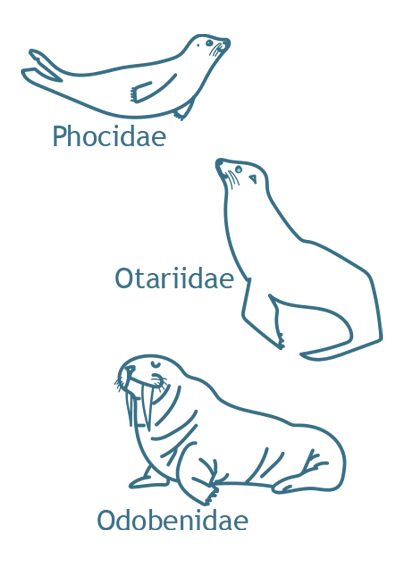

From first appearing around 30 million years ago, seals have spread across the globe with 33 surviving species split into 3 main groups:

True seals (Phocidae) are earless and move on land powered by their fore flippers creating a caterpillar like motion as the move across the land on their bellies (18 species)

Sea lions and fur seals (Otariidae) both have ear flaps and have rotational rear flipper joints so they can stand on all four legs and walk on land. One is furrier than the other! (14 species)

Walrus (Odobenidae) are distinguished by their large tusks and they are the last surviving species of a once much more diverse group (1 species)

Seals have whiskers that proactively move individually and independently of each other to detect fish. True seal whiskers have a wavy shape to enable them to sense the wake of fish 30 seconds and 180 metres in front of them! Seal whiskers are incredibly sensitive with a much higher number of nerve fibres that most other mammals and they are 10 times more sensitive than terrestrial mammals. Seals also have eyebrows – 4, 5 or 6 pairs that help give a 360 degree array around their face accurately sensing the location of prey in front of them.

Seals have an annual catastrophic moult. This means they lose and regrow their entire fur coast over approximately a three week period. Old fur goes brown as it breaks down and loses pigment. More blood is released near the seals skin to facilitate fur growth. As new grey fur grows it pushed the old brown fur out of the follicle. Seal retain the same fur pattern pre and post moult.

Like humans, seal mums have the ‘love’ hormone and neurotransmitter oxytocin. Humans and seals also both have other neurotransmitters in common – dopamine (the ‘feel good’ hormone contributing to feelings of pleasure and motivation), serotonin (important in regulating mood, sleep and digestion) and endorphins (hormones that act as natural pain relievers and mood boosters.)

Seal facts and figures

Seals are utterly amazing and there are so many facts and figures we could bamboozle you with, so we will just pick out 3 of our favourites. There are lots more in the senses, lifecycle and behaviour sections of our website.

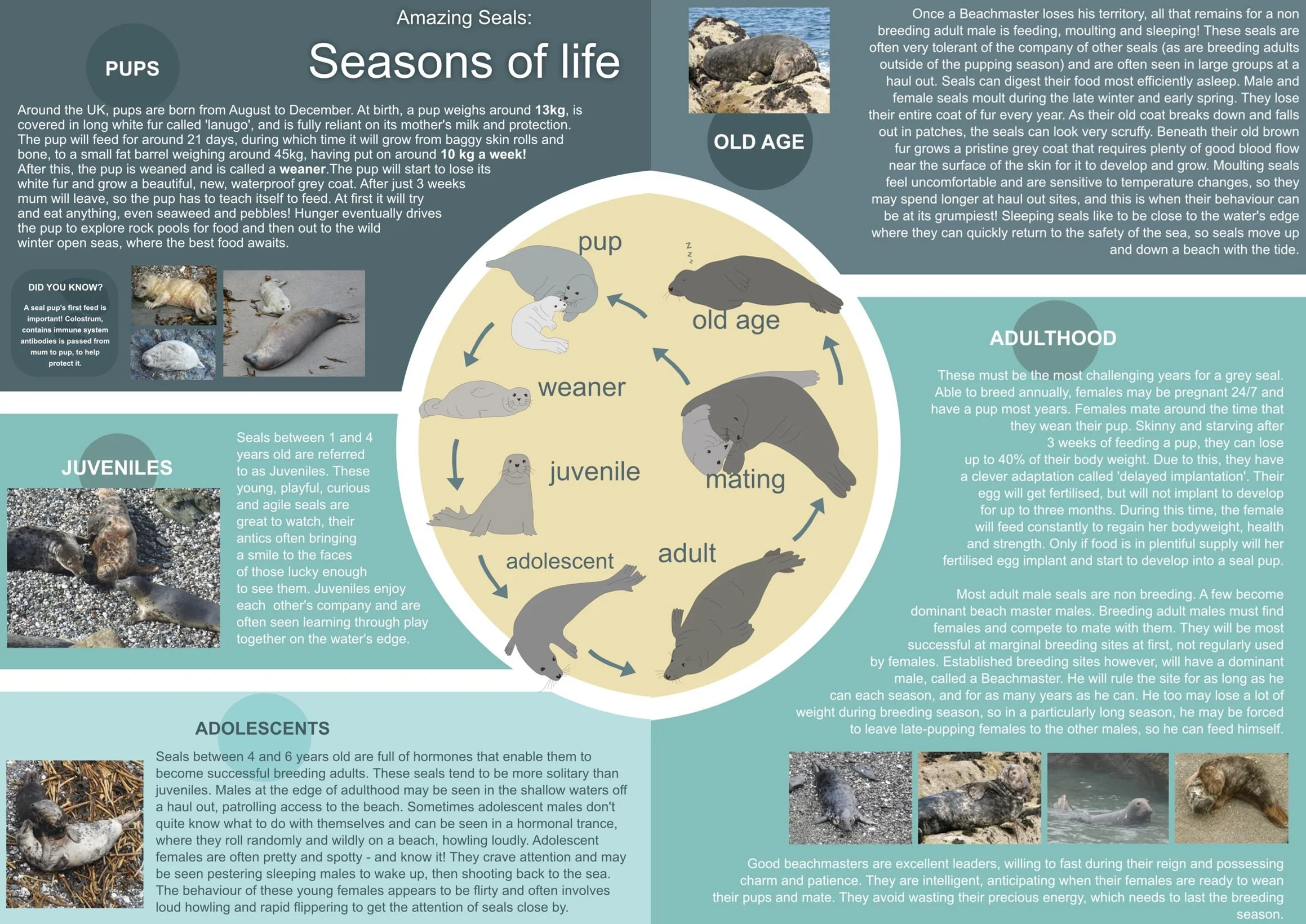

Seal lifecycle

Seal mums mate around the time that they wean their pups. Both UK native species exhibit embryonic diapause (or delayed implantation which can last 2 to 4 months). This gives seal mums time to recover and feed back up to full health before their fertilised egg (blastocyst) implants in their uterine wall where the foetus starts to grow and develop which can take between 7 and 9 months, enabling seal mums to pup on a 12 month cycle.

A straightforward birth can be over in a couple of minutes, but complex births can take a lot longer and in Cornwall one mum was even recorded having passed away whilst pupping, with her pup half in and half out. At birth human baby brains are around 25% developed compared to adult brains. In contrast, Weddel seal pups are born with brains that are 70% developed compared to an adults. This may help explain how a grey seal pup (like SMRU) can be fully functioning at 4 weeks old.

Pups suckle milk from their mothers for between 2 to 3 weeks (for grey seals) and 3 to 5 weeks (for harbour seals). Seal mum’s milk has a very high fat content (around 40 to 50% for harbour seals and 50 to 60% for grey seals compared to 5% in cow’s milk!) Grey seal mums use over 80% of their energy reserves to feed their pups who consume around 71.2 megajoules a day (around 17,000 calories!) Throughout their entire nursing period, grey seal mums don’t actively feed but rather they fast making them a capital breeder. In contrast, harbour seal mums as they continue to forage during their lactation period.

Around the time of weaning from their mothers grey seals lose their long white fur coat, which is called a lanugo. Harbour seals lose their lanugo in utero before they are born.

When seal pups are weaned they are fully functional. One seal pup ‘SMRU’ who was satellite tagged in Bardsey Island in northwest Wales at 3 weeks old, stayed on the beach for another week before swimming north to Anglesey, southwest to southeast Ireland, south to the Isles of Scilly and onto Brittany in northwest France before being rescued from the west side of the Lizard in Cornwall at the grand old age of 12 weeks. In just 8 weeks, SMRU had swum 1000km and routinely dived to 120m.

The only flaw in the plan is that seals mums don’t have time to teach their pups what to eat and how to catch food. So, young seals must use their natural curiosity to feed their hunger.

Weaned seal pups are called weaners. They live of their fat reserves, losing weight whilst they teach themselves to feed. This is the riskiest time of their lives, as they are discovering what to eat and how to catch it, as well as learning to navigate their way around coastal land and sea habitat. If they keep getting disturbed by people, they can waste too much energy and die during their first winter before they have become efficient feeders.

Pups that make it through their first winter become juveniles. Like humans, these youngsters learn through play and are highly curious about everything their encounter on their travels. They had their first annual moult before they were born or as they wean and so their fur has to last more than a year before their next annual moult. As a result their fur can break down and lost all its pigments turning them a golden brown colour or plain. Once they have their second annual moult 12 months later their original fur pattern returns enabling them to be identified for life as each of their fur patterns is unique to them! All our UK seals have solitary lives as they navigate their way around their favourite sites which they seasonally repeat for each life stage. Both species become gregarious as they haul out with other seals where more pairs of eyes increase their safety. Close observation of seals on haul out sites shows how much activity there can be, with regular vocal and nonverbal communication and sealy soap operas playing out.

UK native seals typically reach sexual maturity between the ages of 3 and 7 years. SRT Photo ID experience shows many grey seal females mate at around the age of 5, having their first pup at the age of 6 years. Both UK native seals have a dominance hierarchy among males particularly during the pupping season. Dominant males will routinely patrol pupping sites or parts of pupping sites (depending on the size of the site), seeing off rival males and protecting their pupping mums. Seal society is female dominated, so adult males must treat their females well and look after them to stand any chance of successfully mating with them! Sites with strong, confident and assertive dominant males (called Beachmasters) seem to attract more pupping females who feel secure under their care. These pupping sites are generally calm and organised as a result of the Beachmaster’s excellent leadership. As soon as power is lost, pupping sites become anxious, unsettled places with lots of competing males and stressed out females, fed up of fending the males off all the time.

Female seals do not have a menopause, so they can have a single pup every years (twins are extremely rare but have been recorded and confirmed through DNA analysis). In contrast most adult males are non breeding. Only a few dominant males get to mate with females. This takes considerable energy as they fast throughout the pupping season until they run out of energy. SRT’s observation of Beachmasters is that they rarely dominate a haul out for more than 5 years.

Those seals that are lucky enough to become elderly (particularly males) seems to change their visit patterns and seasonal routines, visiting new sites where they have not been identified before. Sadly SRT and Cornwall Wildlife Trust Marine Strandings data suggests that many males are not reaching old age, which is a concerning ‘red flag’ for us all to learn more about.

Seal behaviours

Seals have an amazing range of different land and sea behaviours as well as transitions between the two.

Hauling

Bananaing ~ This behaviour is most commonly seen on a rising, near high tide! When seals have been resting on land for hours, they are presumably toastie warm and the last thing they need is to be swooshed over by cold water. Much like us they seem to be hesitant to get cold water flushed overtheir most sensitive bits. These are the parts of their body where they have less blubber. Again much like us, this is their faces, hands, feet and bottoms! So they try really hard to keep these out of the water, lifting both their front and back ends above the water lapping around them. Their body forms a curvy banana shape! Some seals appear to resist going back into the sea, and committing their most sensitive bits to the cold, for as long as possible only giving up when they have been floated off their favourite rock! In an ideal world seals will return to the sea slowly, allowing their counter current heat exchange system in their fore flippers to acclimatise themselves to the cold before swimming off! Of course this has implications when we are around hauled seals. If we suddenly spook them into the sea, they have not had time to prepare their bodies for the cold water. This is a key reason why it is important for us to stay at least 100m from hauled seals as this allows them avoid cold shock.

Playing

Sleeping on the land or in the sea ~ Seals routinely sleep on the seabed or at/just below the surface of the sea. They can float horizontally (called logging) or vertically (called bottling). When sleeping on the seabed, seals have sleep cycles that are systematically repeated enabling them to regularly return to the same spot at the surface to breathe before diving back down to their favourite bit of seabed to snooze. Seals can directly detect oxygen levels in their blood (unlike us, who have to use a proxy of carbon dioxide levels) enabling them to return to the surface when they need to breathe. But seals also sleep on the land, where they can rest without having to think about what the water movements are doing. Seals can shut down more of their brain when sleeping on land compared to when they are in the water. On land, seals can switch to bihemispheric slow-wave sleep (BSWS), where both halves of the brain can be asleep simultaneously. This allows for deeper, more restful sleep, similar to other mammals. REM sleep is essential for most mammals’ health. If rats are deprived of REM sleep, they lose weight, suffer hypothermia, and eventually die. On land, seals’ sleep consists of both REM sleep and slow-wave (non-REM) sleep, with 80 minutes of REM sleep a day. In the water, their average amount of REM sleep fell to just 3 minutes a day. That’s less than the rats got during experiments on REM sleep deprivation. Unlike most animals, seals can spend some time with half their brain sleeping like dolphins and some time with their whole brain sleeping! On land seals can spend 38% of the time whole brain sleeping compared to just 6% in the sea where they have to be alert to watch out for predators and to keep their nostrils above water to breathe.

Swimming

Diving ~ Seals make a conscious decision to prepare their body 15 seconds before diving. This involves pooling all their peripheral blood into their core and slowing their heart rate from their at surface average of 120 beats per minute. The deeper the dive, the slower their heart rate – even down to a few beats a minute which effectively shuts off their blood circulation completely. Even grey seal pups a few months old can dive to 280m. Most dives are likely less than 100m where seals feed on the seabed for their favourite seal species. On the east coast of the UK this is sandeels for grey seals and dragonets for harbour seals. Seals have 10 times more red blood cells than humans to store oxygen in their haemoglobin, but they can also store more oxygen in the myoglobin in their muscles (where it is needed for activity) than humans can.

Hauling ~ Seals use their fore flippers to lift themselves up, lunging forwards on their bellies in a caterpillar like motion across the land, dragging their rear flippers behind them. Seals can climb up surprisingly steep, slippery and uneven rocks. After hauling out seals go through a relaxation routine that invariably involves rolling over, stretching, yawning, head rubbing and scratching. Seals’ spines are incredibly flexible, much like a cats. As they first emerge from the sea, seals open and close their nostrils to smell who and what is on the haul out. They will manoeuvre themselves around the haul out, sometimes greeting, and sometimes avoiding other seals. If they consider themselves to be safe they will begin rolling onto their sides or back or even wriggling around to cover themselves in substrate. As they relax, they can be seen doing really elaborate stretches that can even find them touching their own toes! Stretches are often accompanied by very wide 70 degree mouth open yawns and slow head rubs as they open their fore flippers stretching forward up and over their faces. As their fur dries out, especially during the moulting season, these haul out rituals are accompanied by scratching any part of their body accessible with the fore flippers or by doing ‘sand angels’ for inaccessible back rubs and rear flipper swooshing for itchy bottoms! It takes a lot of energy hauling out, so the last thing seals need is to be disturbed by us back into the sea. SRT’s Photo ID work suggests that most seals will not re-haul out once disturbance (presumably for safety reasons).

Bananaing

Playing ~ Juveniles love playing with each other in male/male and male/female partnerships. Females are rarely observed playing together. Even adult males seem to enjoy playing with each other outside of the pupping season. We think females are just too busy feeding pups and growing their next pup to waste energy playing. They will swim in agile circles around each other in the sea or side on with each other. Two seems the ideal number with 3 being a crowd, but this doesn’t stop them! They will also play with things they encounter such as seaweed or lost and active fishing gear (which poses a much bigger threat to their safety.) Seals play on land too, even doing roly polys, where one seal lunges up onto of another at right angles – one moving the other like a rolling pin!

Logging

Swimming ~ Seals use their rear flippers to propel them through the water. Their open webbed rear flippers are held vertically upright. These are then fanned back alternately to push them forwards. On very calm days you can see the wake they create. As highly mobile marine mammals, seals can swim at top speeds of 25km an hour for 100km a day. One seal ‘Sate’ swam the entire Cornish coast (approx. 700km) in 4 days. We know this because he had a satellite tag.) Incredibly Sate visited 3 countries (France, England and Eire) and 3 English Counties (Cornwall, Devon and Dorset) in less than 4 months.